How UMMA Clinic Looks Upstream: The Black Visions of Wellness Program

An African American patient comes in with a chronic medical condition and is having a hard time coping with the prognosis. She had been struggling with her health for a few years, battling hypertension and trying to lose weight. Her chart is handed over to one of the clinicians at UMMA Community Clinic. He sees her and talks to her about how she is doing. He asks the typical questions, but answering those questions proves to be a bit emotional for the patient. Realizing that she could use some support, a thought sparks his mind. It’s the perfect scenario to enroll her into the Black Visions of Wellness program.

What is the Black Visions of Wellness program (BVOW)? It is an integrated model of care that involves not only doctors, but health educators and non-traditional health care providers to heal patients holistically. Participants of the program are local residents in LA County, identify as African or African American, and are already under the UMMA umbrella of care through Medi-Cal. The program itself aims to reduce the burden of illness caused by chronic conditions while providing counseling for emotional and mental distress as well as substance abuse.

In the four years of BVOW’s existence, the program has seen the incredible growth within participants, like the aforementioned patient story. Currently, there are nearly 80 participants enjoying benefits like free YMCA memberships, free health education and cooking classes, free exercise classes including Zumba and Tai Chi, and free alternative medicine procedures such as chiropractic and acupuncture. In addition to these non-traditional services, participants partake in challenges like the annual 13-week Weight Loss program. Moreover, participants have access to culturally competent and experienced therapists and doctors.

A program like BVOW is not only unique and innovative, but also exactly what the Upstreamist movement needs. The Upstreamist movement, galvanized by Dr. Rishi Manchanda who himself served as a physician in South-Central Los Angeles, believes in the power of providers to connect to a patient’s full background—beyond medical history. Drawing on the framework of the social determinants of health, Dr. Manchanda encourages Upstreamist providers to investigate disease etiology through closer inspection of patients’ living and working conditions and other context clues from their lives. Through this comprehensive approach, he believes that a more effective model of care is achieved.

Take, for example, one patient that presented her story to Dr. Manchanda. In his TED talk, Dr. Manchanda recounts this experience by talking about how his patient had been to the Emergency Room twice due to recurring excruciating headaches—all in a span of a few weeks. ER doctors did routine tests and labs to no avail. No diagnosis was made and the patient returned to her home no better than when she had left. She then came to him, where he asked her questions about her living conditions and any allergies she may have been experiencing. As it turned out, the patient was living in toxic conditions; mold engulfed her apartment. Dr. Manchanda did something then that many other doctors do—he wrote a referral for a specialist.

Dr. Manchanda’s referral was no ordinary referral, though. The “specialist” he referred her to was the City mold inspector, so that they could come and report the hazardous conditions in which the patient lived. Such a referral would not only target the root of the problem, but would also connect the dots between personal health to public health. This connection is all too often missed by doctors. And when this connection is missed, so too is the social justice for marginalized and neglected communities—Dr. Manchanda realized this. Dr. Manchanda, however, is not the first or only doctor to have made such a referral.

In the early 60s, at the heart of the civil rights movement, a young doctor by the name of Jack Geiger began seeing patients at a community health center in rural Mississippi. The first ever of its kind, the community health center was based on a model developed in then-apartheid South Africa, where indigent and marginalized communities received access to healthcare through local clinics. Having realized that race and socioeconomic status were the social determinants of health, Dr. Geiger developed an idea to help the underprivileged patients in Missouri who were suffering from malnutrition. His idea? To write prescriptions for groceries so that his patients could get the real “medicine” they needed.

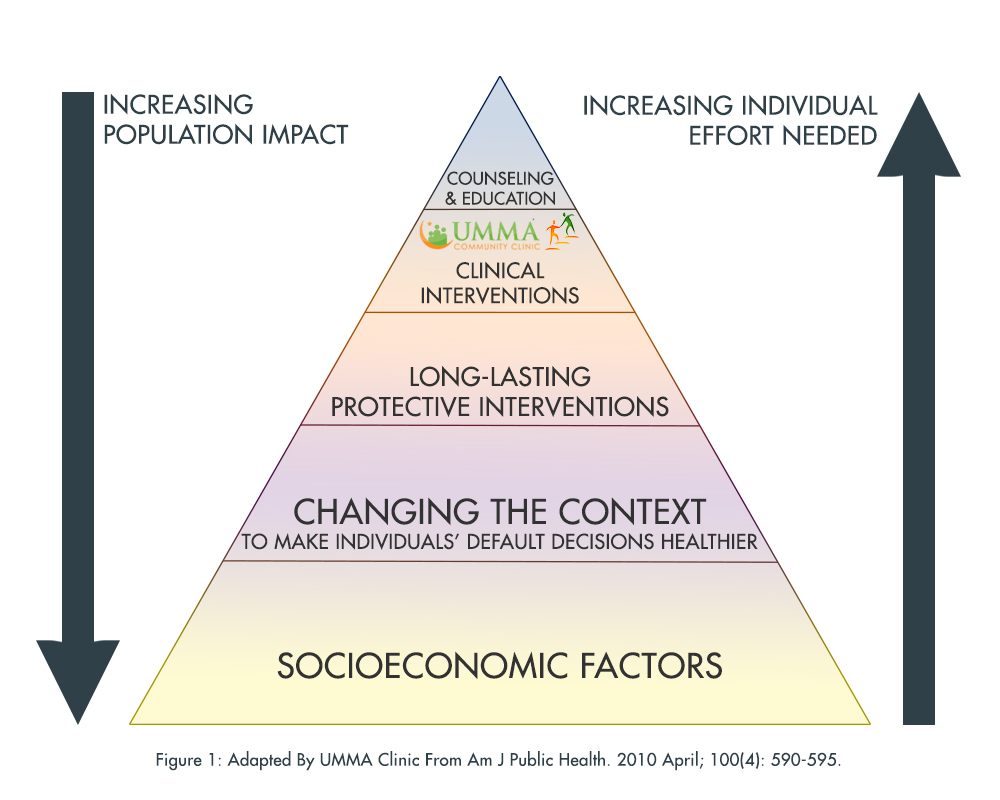

So, then, what do both Dr. Manchanda and Dr. Geiger have in common? Their focus on health looks upstream, noting that it is, in fact, the social determinants of health that affect public health at large which inevitably trickles down to the individual patients they see. It is, in fact, not the individual who is responsible for the many diseases and symptoms they experience; rather, it is an entire political, economic and social ecosystem that institutionalizes their destitution and therefore cultivates the exact environment for their chronic conditions to develop. Both doctors acknowledge the role of the social determinants of health—as established by such revered researchers like Sir Michael Marmot who was knighted for his research on the social gradient of health, Dr. Thomas Farley who wrote a book entitled Prescription for a Healthy Nation, and Dr. Friedman, who developed a model known as the health impact pyramid (below).

In ascending order are interventions that change the context to make individuals’ default decisions healthy, clinical interventions that require limited contact but confer long-term protection, ongoing direct clinical care, and health education and counseling. (CITATION: Am J Public Health. 2010 April; 100(4): 590–595)

The health impact pyramid is perhaps the most succinct visualization of what the BVOW program and the Upstreamist movements are all about. If more doctors received public health training to understand how socioeconominc factors lead to chronic disease (the bottom tier of the pyramid), then perhaps less prescriptions for medications would be written and more referrals for “specialists” would occur. Amazingly, this is already happening at UMMA Community Clinic! The specialists within the network of the BVOW program are at the “clinical interventions” tier, which include all of the alternative care providers, the health educators and the health class instructors (the top tier of the pyramid)—all of whom are writing the “prescriptions” and “referrals” to the “counseling and education tier” in order for BVOW participants to address their immediate and long term health concerns.

The BVOW program is a great way to implement the principles from the Upstreamist movement on a larger scale. The Upstreamist movement seeks to recalibrate doctors from being pathologists of disease to pathologists of socioeconomic factors; if it were to implement this recalibration to beyond doctors to entire programs like Black Visions of Wellness, many patients would benefit as would healthcare centers and community clinics. The reorientation of medicine is a revolution not just for doctors, then, but for the entire healthcare system. Looking upstream need no longer be the duty of any one physician, but an entire support system of specialists and programs alike that work in tandem to address the health conditions of patients.

With such a system, there would be a continuum of medicine on one end and social justice on another. At UMMA Community Clinic, this continuum already exists—however, many more Upstreamist doctors and programs need to develop in order to truly start a healthcare revolution. With the social determinants framework, social justice becomes intertwined with a higher standard of medical care—and that’s how it should be.

By: Amelia Noor-Oshiro